When I was fourteen years old, I started to learn Russian. For the first seven weeks, I spent four hours a week in a classroom with five other pupils and a teacher. It was a very interesting classroom. No English was spoken by the teacher or the pupils. That is not unusual in language classrooms, where the use of the target language only is not uncommon. It was also not unusual for there to be lots of pictures to support learning, though that was harder for a teacher in the 1970s when we did not have computers in schools. My teacher relied entirely on pictures cut out of Sunday supplements. What was relatively unusual was that there was absolutely no reading or writing of any kind in those seven weeks, not even an A for apple or a B for ball. We looked at pictures, we listened to our teacher and eventually we responded in Russian to his questions about the pictures. We learned to make sounds in Russian that do not exist in English. We learned to conjugate Russian verbs and decline Russian nouns. The word for ‘sit’ in Russian depends on who is doing the sitting and the word for football changes, depending on whether you are playing or talking about it. All these year later, I can still reel off the Russian for “My dad and my uncle are sitting on the sofa talking about football” without thinking about it. It was wonderful teaching that understood immersion is how we learn language as a small child and it works for learning other languages too.[1] Reading and writing in the Cyrillic script that Russian uses had to wait and was much easier when we started it because we already knew lots of words.

My fantastic Russian teacher, Mr Howard, was also one of my French teachers. We learnt French differently with lots of reading, writing and grammar. Nonetheless, I passed my French A level and then went to live in a Paris for a year. Thanks to some very good French teaching, I could follow Racine at the theatre and understand the nuances in an opinion piece in Le Monde. I could just about shop in French but working in a warehouse was much harder. On my first day at Thé Twining I realised that I barely understood a word of what my colleagues were saying. It wasn’t that there was a range of accents (though there are issues with acquiring your French from Spanish and Portuguese migrants) or even that I didn’t know how to swear in French at that stage. I just wasn’t used to living or working in French. My French got much better very quickly. I even started to dream in French. Towards the end of my time in Paris I spent a lot of time in bars- honestly, only because I did not have a television and I wanted to watch the 1978 World Cup. I came home after the semi-finals. My brother-in-law met me at the station in London and I wanted to ask him if we would be home in time for the third place play-off match, but I could only remember how to say it in French.

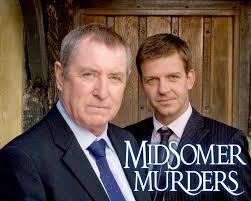

I was reminded of the importance of immersion in language learning recently by Hannah Sharma, the Vice-Principal at Trinity Academy. The school has a large number of EAL learners and Hannah was concerned that that many Spanish and Portuguese speaking pupils now learning from home would have no opportunities to be immersed in English as they are at school. It is a problem now facing many schools in the UK and many British international schools around the world. There is no easy solution, but our recent work in Denmark suggests one way forward. Most of the Danes I speak to, especially those under 50, have amazingly fluent English. They make errors very rarely and have good English or American accents. When I ask them why their English is so good, they often mention starting to learn it an early age and having good teachers. They also always mention television. Denmark is a small country with a small TV industry. While Denmark exports my favourite crime programmes (I love The Killing), it also imports a lot of American and English programmes. When I am working in Denmark and switch the TV on in my hotel room, there is always a John Nettles era episode of Midsomer Murders on and it is always subtitled rather than dubbed. The thing about good television and video is that you get immersed in it. While you are immersed you are learning the language.

So that’s how I think you learn to communicate in another language, but I do need to say immersion is not enough to teach you the kind of language you need for study and doing well in exams. Someone has to teach you how academic English works, but that is for another blog.

[1] If are interested in the academic underpinning of this approach, a good place to start is Stephen Krashen’s Principles and Practice in Second Language Acquisition