There is widespread myth about this country and its people. It is the myth of a monolingual island race with its world conquering language, which over a billion people speak world wide as an additional language. The billion additional language bit is, of course, true, but it is not so much a legacy of the British Empire as a consequence of American economic power.

The relationship between language learning and economic power has long been known. John Gallagher’s Learning Languages in Early Modern England[1] tells us “early modern England was multilingual” because it needed to be. The explosion of language learning that Gallagher describes was a response to England’s status as a fairly minor economic power in the sixteenth century. The country needed international trade and that was not possible without learning other languages.

The advice about learning French in the sixteenth century was, according to Gallagher: get a French bible and go to a French church every day. That was relatively easy in London as there was a large French speaking community with lots of churches in which you could immerse yourself in the language. There were Dutch and Italian churches too.

One brief version of the early history of English goes something like this: a range of Celtic languages (including Welsh, Gaelic and Cornish) give way as Germanic tribes invade to multiple dialects of Anglo-Saxon. The Vikings come and Anglo-Saxon vocabulary takes on Scandinavian words (e.g., place names ending in thorpe). David Crystal’s account of the development of English is an excellent guide.[2]

Where I live now in Walthamstow we have Polish, Bulgarian and Romanian shops, Sunni and Shia mosques and a church with services in Urdu.

Our independent schools now have Chinese pupils in large numbers now, not just as boarders but as day pupils, especially in schools near Reading (where Huawei has its European HQ- economic power matters for language now, just as in the sixteenth century).

Britain has always been and always will be multilingual. To pretend otherwise is to follow in the footsteps of one of our least successful Anglo-Saxon kings, the Danish born and speaking Cnut. The king who thought he could stop the tide coming in is far from only British monarch whose first language was not English.

What does this all mean for us as EAL professionals?

The Council of Europe’s Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR)[4] distinguishes between multilingualism (the coexistence of different languages at the social or individual level) and plurilingualism (the dynamic and developing linguistic repertoire of an individual user/learner). It has helped me to think about how EAL practice has developed over the last fifty years in Britain.

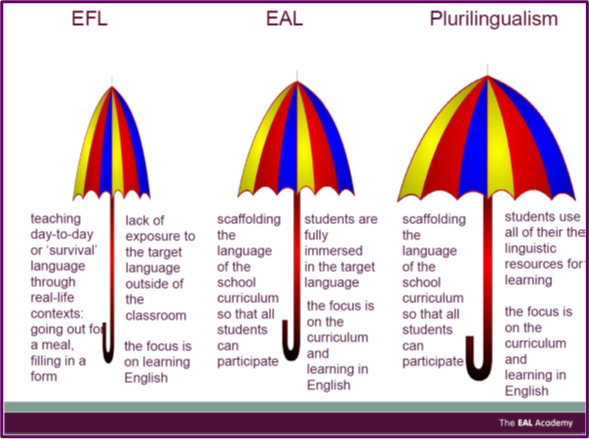

What we call EAL started under the first umbrella. It is not very helpful for understanding science, mathematics, history or any other subjects. NALDIC’s[5] work over the last 27 years has been central to shifting EAL to the second umbrella, correctly arguing that EAL is about learning in a curriculum that is in English, not simply learning English. 25 years ago I wrote my first and very NALDIC friendly language across the curriculum policy for the school I was then working in: it acknowledged and celebrated the school’s linguistic diversity, but could have done a lot more practically to encourage it, particularly given the multilingual nature of the staff and their plurilingual staffroom conversations in our 84% EAL school. The practice The EAL Academy promotes now fits under the third umbrella, not because I am virtuous or right, but simply because that is how the world we live in really is.

The three umbrellas also throw up a in issue about what we believe EAL as a discipline is. My view is that effective EAL practice is effective school improvement practice. It is not about giving pupils enough English to cope in the mainstream classroom because no one can really say what enough is.[6] EAL, therefore, has to be about transforming teaching across the curriculum. Disciplinarity, in current Ofsted speak, means very little if it does not include knowing how to read and write and above all how to make meaning in specific subjects.

[1] John Gallagher (2019), Learning Languages in Early Modern England, Oxford University Press

[2] David Crystal (2004), The Stories of English, Allen Lane

[3] Farah Nazir (2020) https://ealjournal.org/2020/11/11/language-homes-pahari-pothwari-and-english/

[4] https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages/level-descriptions

[5] https://naldic.org.uk/

[6] The CEFR scales are about general language performance, not the understanding of curriculum subjects and subject specific language practices.