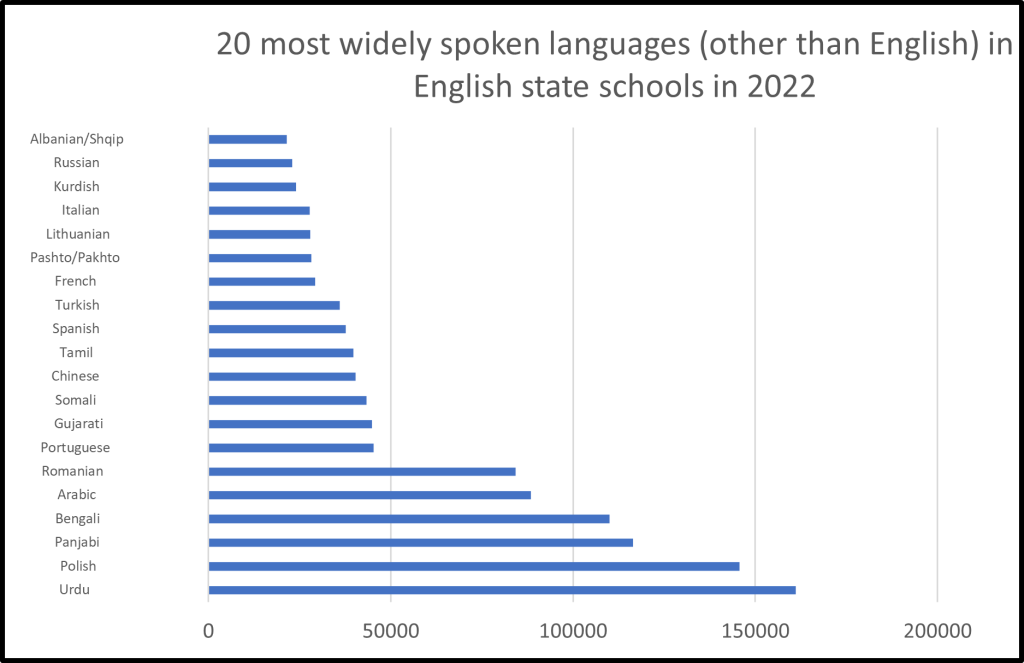

The 2021 school census (DfE, 2021a) records 316 languages spoken by pupils and acknowledges that there are more. It tells us that pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) make up 19 per cent of the state school population in England, pupils with free school meals 21 per cent and pupils with SEND 12 per cent. For the last two of these groups of pupils, additional funding is available throughout their time in school. For EAL pupils, much lower levels of funding are available and only for their first three years in school. EAL is not a condition that can be fixed by a bit of extra support for three years. It is a very positive fact of life in multilingual Britain. I will argue that the best EAL practice involves strategic thinking about pupils and the multilingual environment that they inhabit. It is not about three years of acquiring enough English. After all, what is enough English? Lynne Cameron and Sharon Besser’s study (2004) of Key Stage 2 test scripts tells us that EAL pupils with at least five years of UK schooling (a group including many who started school in Reception) were significantly more likely to omit prepositions or use them incorrectly in formulaic phrases such as ‘ashamed of’ or ‘on purpose’. Good EAL provision should meet the needs of all multilingual pupils, from those new to English to those still fine-tuning their grasp of both day-to-day English and academic English. Indeed, the large-scale research (see, for example, Collier and Thomas, 2002 and Strand and Lindorff, 2021) suggests four to six or seven years for a pupil to catch up if already literate in the mother tongue and longer if not. It is much more helpful to see EAL as being a fact of life in modern multilingual Britain, and to think of the school practice that we call EAL as being about teaching pupils how to learn effectively in English and secure control of the academic language that they need across the curriculum.

The debate about EAL is not helped by the fact that there is no mention of it in the current Ofsted framework (2019). Roughly two and a half per cent of reports written under the current framework actually mention pupils with EAL (Watchsted, 2021). In around half of those cases, the mention comes quite inappropriately in a paragraph (and sometimes a sentence) about SEND.

An informed reading of the language data in the census, cross-refenced with ethnicity data, would suggest that that there are many more EAL pupils than the 19 per cent census figure suggests. The DfE’s definition of EAL for the school census purposes is: ‘where the pupil has been exposed to a language other than English during early development and continues to be exposed to this language in the home or in the community’ (2021b). An analysis of the proficiency codes (from A for beginner to E for fluent), no longer required by the DfE but still widely used in schools, provides further emphasis: ‘A pupil is recorded as having English as an additional language if she/he is exposed to a language at home that is known or believed to be other than English. It is not a measure of English language proficiency or a good proxy for recent immigration.’ (DfE, 2020, p. 4)

It’s a helpful definition that reminds us that we live in a multilingual country. Some schools are very good at gathering the information and languages because they understand how strategically important it is. At St Michael’s RC Primary in Newcastle (www.st-michaels.school), they have a bank of questions to ask, including:

- Which are the main languages used at home?

- Which languages are used by which different members of the family?

- Which language does the child watch television in?

- Who reads and writes which languages in the family?

They also ask about the languages in the child’s prior education. St Michael’s is a school where over 57 per cent of pupils have free school meals and 58 per cent have English as an additional language. Attainment and progress at the end of Key Stage 2 are both well above the national average. What they do works.

The 2021 school census (DfE, 2021a) tells us that 64.9 per cent of pupils are White British. Occasionally one of these pupils will have EAL. The pupil may have lived in another country and received all of their prior schooling in another language. However, such cases are very rare. Nonetheless, if you add Black Caribbean pupils to the 64.9 per cent White British, along with some of the mixed groups as very likely being native English speakers plus the unknowns, you get a minimum figure for the ‘not EAL’ group of 70 per cent – which leaves you with a true EAL figure somewhere between the recorded 19 per cent and 30 per cent. If all schools adopted St Michael’s approach, I suspect that we would have a figure in excess of 25 per cent. Why does this matter? Our approach to learning should be informed by secure knowledge of the full linguistic repertoire of all our pupils. The evidence about the positive impact on learning of knowing more than one language is legion (for example, Bak and Mehmedbegovic, 2017).

In the Pakistani households in the streets where I live, the situation may often be something like this: the children may only talk to Grandma in Panjabi because she can’t speak anything else; one of the parents is UK-born and educated and the other is not; the parents want their children to understand and be literate in Urdu; the children speak English at school and to their parents some of the time; films in Hindi are watched regularly; at the mosque and the madrassa, they encounter Qu’ranic Arabic. That is all before you consider the fact that there are five Panjabi options in the school census: Panjabi, Panjabi (Any Other), Panjabi (Gurmukhi), Panjabi (Mirpuri) and Panjabi (Pothwari).

To summarise so far, EAL is more complex and more common than we think or record, and EAL pupils have more diverse needs than the government acknowledges. What are the implications for schools and teachers? We are fortunate that a major new book by Robert Sharples (2021) contains an excellent summary of current research and an informed awareness of what the best EAL practitioners are doing.

The book starts with a brief history of the thing that we call English as an additional language, followed by an overview of what research tells us about language acquisition. We are walked through a theory of language with Noam Chomsky (see Evans, 2014 for the difficulties associated with Chomsky’s approach to studying language) and what a range of key research tells us about acquiring a first language and a subsequent language (although let’s not forget that many children grow up learning more than one language at home).

Part 2, ‘Language across the curriculum’, is for me the key section of the book. We are safely in the company of figures such as Jim Cummins (2000), with his emphasis on distinguishing the cognitive and contextual demands of learning, and Michael Halliday (cited in Sharples, 2021). Halliday’s work in the field of systemic functional linguistics assumes, in contract to Chomsky’s approach, that we should study how real people do actually communicate. It is underpinned by the notion that meaning is always created in a specific context. For detailed, classroom-based examples of this approach, see Daborn et al. (2020) and Derewianka and Jones (2012). What I take from it is that EAL is not so much about teaching English as it is about teaching pupils how to learn successfully in English. That is very different to acquiring ‘enough English’. It makes the curriculum accessible and equips pupils to make sense of complex and often multimodal texts. It teaches them to speak and write academic language.

The final section, ‘The EAL specialist’, works through the practicalities of being responsible for EAL in a school, covering issues such as welcoming new arrivals and setting up an effective assessment system. These matters understandably cause the greatest anxiety in schools, but too sharp a focus on them at the expense of meetings the needs of pupils with a growing grasp of English can have negative consequences for both individual and institutional outcomes in tests and exams.

One way of thinking about the changing approach to EAL is that we have moved from a time when most pupils new to English were sent to special centres, away from pupils from whom they could learn everyday English, to be taught ‘enough English’. The approach was called EFL or ESL (English as a foreign language or English as a second language): it did not work. EAL has become an approach focused on immersion in English socially and the scaffolding of both the language and the content of the curriculum. The next step is widespread acknowledgement in schools of the multilingual nature of Britain and encouraging pupils to use all of their languages and linguistic resources in their learning. This approach to EAL has benefits for all learners, including those brought up speaking only English. Perhaps that is what the eminent French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu had in mind when he reminded us that ‘Academic language… is no one’s mother tongue.’ (Bourdieu and Passeron, 1994, page 8).

FIrst published in Impact, the Journal of the Chartered College of Teaching

Author: Graham Smith, Director of The EAL Academy

References

Bak T and Mehmedbegovic D (2017) Healthy linguistic diet: The value of linguistic diversity and language learning across the lifespan. Languages, Society & Policy. DOI: 10.17863/CAM.9854.

Bourdieu P and Passeron J-C (1994) Introduction: Language and relationship to language on the teaching situation. In: Bourdieu P, Passeron J-C and Saint Martin M (eds) Academic Discourse: Linguistic Misunderstanding And Professorial Power. Polity.

Cameron L and Besser S (2004) Writing in English as an additional language at Key Stage 2. DfES. Available at: www.naldic.org.uk/Resources/NALDIC/Research%20and%20Information/Documents/RR586.pdf (accessed 20 April 2022).

Collier V and Thomas W (2002) A national study of school effectiveness for language minority students’ long-term academic achievement. Available at: thomasandcollier.com/s/2002_thomas-and-collier_2002-final-report.pdf (accessed 20 April 2022).

Cummins J (2000) Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

Daborn E, Zacharias S and Crichton H (2020) Subject Literacy in Culturally Diverse Secondary Schools: Supporting EAL Learners. Bloomsbury Academic.

Department for Education (DfE) (2020) English proficiency of pupils with English as an additional language. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-proficiency-pupils-with-english-as-additional-language (accessed 20 April 2022).

Department for Education (DfE) (2021a) Schools, pupils and their characteristics: January 2021. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/statistics/schools-pupils-and-their-characteristics-january-2021 (accessed 20 April 2022).

Department for Education (DfE) (2021b) Complete the school census: Data items 2021 to 2022. Available at: www.gov.uk/guidance/complete-the-school-census/data-items-2021-to-2022 (accessed 20 April 2022).

Derewianka B and Jones P (2012) Teaching Language in Context. Oxford University Press.

Evans V (2014) The Language Myth: Why Language is not an Instinct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ofsted (2019) Education inspection framework. Available at: gov.uk/government/publications/education-inspection-framework/education-inspection-framework (accessed 20 April 2022).

Sharples R (2021) Teaching EAL: Evidence-Based Strategies for the Classroom and School.

Strand S and Lindorff A (2021) English as an additional language, proficiency in English and rate of progression: Pupil, school and LA variation. The Bell Foundation. Available at: www.bell-foundation.org.uk/eal-programme/research/english-as-an-additional-language-proficiency-in-english-and-rate-of-progression-pupil-school-and-la-variation (accessed 20 April 2022).

Watchsted (2021)

(2019) Breaking down barriers: Why do we classify some languages as ‘community’ and others as ‘modern’? In: IOEBlog. Available at: blogs.ucl.ac.uk/ioe/2021/12/09/breaking-down-barriers-why-do-we-classify-some-languages-as-community-and-others-as-modern (accessed 20 April 2022).

Further resources

You can find a breakdown of the languages spoken in each local authority among our free downloads here.

<< You can hear the headteacher of St Michael’s talking about her school’s approach to EAL in this video.

Download St Michael’s new arrivals questions bank from our free resources here.

Looking for a comprehensive EAL course?

We offer a six month, part time course covering a range of EAL topics.